The dystopian business of bottled air

Soaring air pollution is a city around the world that is leading some people to seek innovation, filling air into an expensive solution

February 3, 2017

Do you know how the filling machines work?

February 3, 2017

On a hazy morning in mid-October, Xiu Wang walks briskly through the streets of Beijing’s Dongcheng District. She carries the requisite luggage of her daily commute: A small backpack, headphones, and a can of fresh Canadian air.

Every 10 to 15 minutes she pauses, pulls her face mask to the side, and inhales a short burst from the can — enough to offer temporary respite from the city’s smog.

On certain days in northern China, the air is so thick with pollutants that Xiu can’t see her own hand in front of her face. Skyscrapers are obscured and flights are cancelled. Environmentalists have dubbed it the “airpocalypse.”

And in the midst of this crisis, a dystopian industry has emerged: Entrepreneurs from less-polluted countries are turning clean air into a commodity.

“We created the market”

In 2014, Moses Lam and Troy Paquette — both Canadian mortgage specialists in their late 20s — were looking for a career change.

“We were kind of just sitting around thinking about things, and saw a bottle of water,” Lam recalls. “I thought, ‘What if we do the same thing, except with air?’”

They loaded into Paquette’s SUV, drove to Banff National Park in the Canadian Rockies, and spent an hour “flailing a plastic bag around, trying to catch the mountain breeze.” The duo listed the product of their labor — a Ziploc of air — on eBay, where it generated some unexpected press and sold for US$130.

“We almost felt bad the guy paid that much money for a bag of air,” says Lam. “But we also saw a business opportunity.”

What began as a joke segued to a full-fledged operation: Lam and Paquette conducted market research on areas with poor air quality. They designed an aluminum can with a patented inhalation nozzle. And in early 2015, they launched Vitality Air, a company that promised to “enhance vitality one breath at a time.”

The audacity of selling a free, natural resource to pollutant-ridden international metropoles was a hit with the media; within a few months, Vitality Air had a 5k-bottle order from China, and pending deals in India, Korea, Vietnam, and Mexico.

The air business

When Vitality first started, Lam and Paquette would suck up air with a $400 tool, transport it to their garage, and manually transfer it into bottles.

Today, they use a $65k, 200-liter machine that collects 21 bottles of air per minute. Affixed to a 24-foot trailer — 12k pounds, fully loaded — the air is brought to Vitality’s new, fully-automated bottling plant.

“We want to keep it as pure as possible,” says Lam. “We’re not taking dirty air and filtering it to make it clean. We’re literally taking clean and pristine air from one side of the world and moving it to the other.”

The company’s core product, an 8-liter can of Banff mountain air, is good for 160 one-second “inhalations” and retails for $32 — or about $0.20 per breath.

Since launching, Vitality’s sales have doubled year over year, from 30k cans in 2015 to more than 200k cans in 2017. This year, the company has invested more than $1m in an expansion effort that Lam expects will “make bottled air the next bottled water.”

Vitality isn’t the only company capitalizing on the “market opportunity” of air pollution.

Down under, in Australia, Clean & Green bottles air from Blue Mountains of Sydney and runs a thriving business exporting it in bulk to Asia ($72 for a 12-can “bundle”).

The company’s founder, John Dickinson, was struck with the idea when his partner called him from the smog-choked reaches of Northern China, and asked, ‘How can people live like this?’

Leo De Watts, a self-proclaimed “air farmer,” collects “ambient breeze” from the rolling hills of Dorset, Somerset, and Wales in non-porous fishing nets, and sells it in artisanal jars for £95 (US $120) a pop.

His company, Aethaer, is named after the Greek god of “pure upper air” — or the superior air that deities breathe. De Watts calls his product the “Louis Vuitton of air.”

“Clean air is now a premium product, since 95% of the world’s population doesn’t have access to it,” he tells us. “If a resource we depend upon becomes more rare, then naturally that resource increases in its perceived value and becomes more expensive.”

A band-aid solution

The goal of bottled air, explains Lam, is not to “be a solution to pollution,” but rather to provide a “fun experience.”

“We want our customers to share our air with their friends and family — to enjoy the taste of fresh air together,” he says. “We’re like Starbucks… it’s a treat.”

Most air entrepreneurs I talk to speak in terms of market capitalization, weakly couched in a desire to “do good” for the world. When I ask Lam about his larger mission, he reverts to economic groupspeak.

“We’re just at the tip of the iceberg,” he says. “We haven’t really cracked China or India. Even if we were to do 0.5% of market share, we’d be looking at 3 to 4m bottles per country.”

Unlike the medical oxygen market, the canned air market operates largely without regulation. Though studies have shown that clean air is preferable to polluted air, the ‘advantages’ of huffing bursts of it from a can are unfounded.

“There are no studies to suggest that breathing clean air from a can in short bursts has health benefits,” Dr. Shawn Aaron, the director of the Canadian Respiratory Research Network, tells us in an email. “It is hard for me to imagine that a few breaths from a can of clean air can mitigate the long-term health risks of chronic pollution exposure.”

In fact, it is likely that Vitality adds to air pollution through their manufacturing and shipping process.

Lam counters this narrative by citing that his bottles are recyclable and contain no CFCs — but there is an undeniable irony in peddling respite to people while adding to the global carbon footprint through international shipments.

De Watts, of Aethaer, claims that his product aims to alleviate global pollution by drawing attention to the issue and raising awareness.

“We are all goldfish living in a murky tank, and we are over-feeding ourselves when it comes to energy creation and product production,” he says. “ You can treat the symptoms, but I want to stop the over-feeding.”

To date, De Watts has only sold about $30k worth of air — but the product directs traffic to his suite of other pollution-related offerings: Face masks, air filters, and an app that tracks air quality.

The commoditization of natural resources

When I talk to Lam, he’s preparing for the Christmas of his industry.

“It’s pollution season,” he says. “Come November, the weather gets colder and the coal plants heat up in Asia. Pollution jumps, and our sales jump. It’s a yearly ritual for us.”

In China, residents like Xiu Wang brace for the thickening of the air with particulate matter, the black nose-blows, the coughing, the masks.

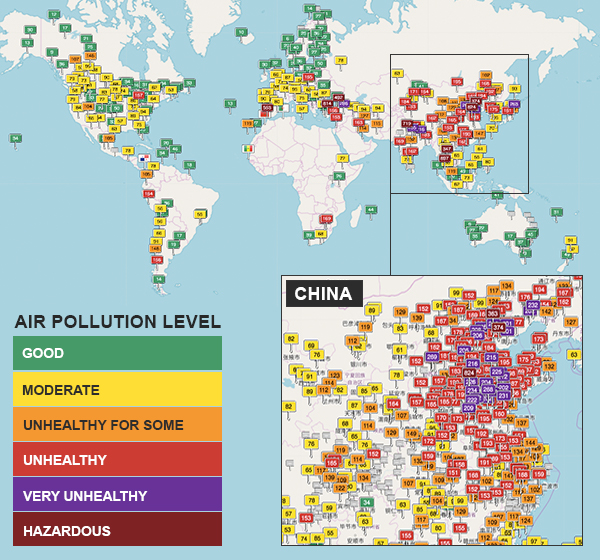

Of the 500 cities with the worst air pollution, China occupies 285 spots. Nearly 40% of China’s population is subjected to air that is, by Air Quality Index standards, “very unhealthy” or “hazardous” — so much so, that a 2015 study found air pollution accounts for 1.6m deaths in China per year.

In a warehouse in Canada, Vitality is ramping up production.

Lam envisions a future where China’s residents will cart around 8-hour canisters of Canadian mountain air, breathing intermittently through nozzles. He’s currently looking into the viability of refill stations, where people could “tap their credit card and get their tanks refilled.”

“I want to be known as the king of air,” he told The Guardian. “I want to be the first person in the world to sell people air.”